James A. George

We all agree that the only way a participatory democracy can possibly work is, not to be too obvious about it, for its citizens to be active participants in its processes, institutions and debates.

While I would be interested in the experiences of others, I can only go on the basis of my own observations of the stark contrast between the number of citizens who loudly proclaim their opinions in the comfy confines of dinner parties and similar social gatherings and the comparatively, almost-non-existent numbers who actually attend meetings and actually go to the podium and actually express their views, whether “our betters” like them or not.

The right to speak out against perceived wrongs committed by those in authority is one of our most cherished rights, and the Founders regarded it as such a basic tenet of freedom that they enshrined it in the Bill of Rights:

“Congress shall make no law….abridging…the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.” First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States

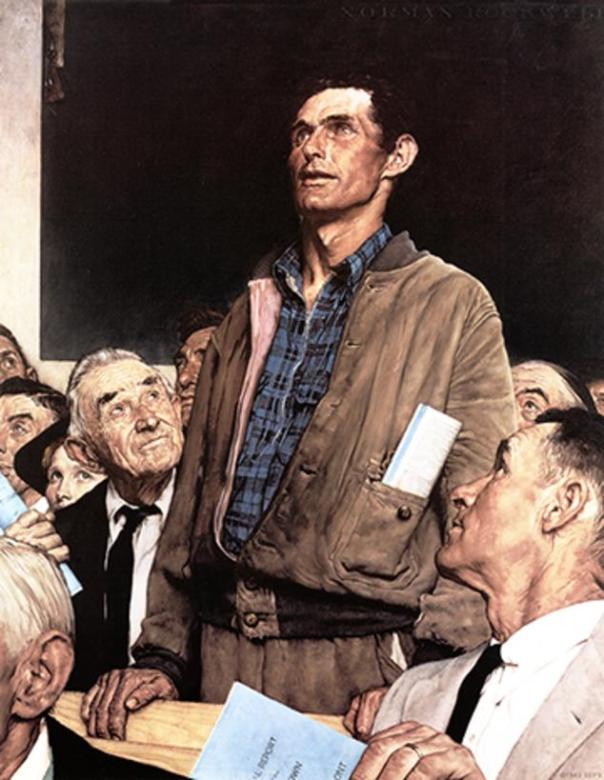

The iconic illustration of that right was rendered by the legendary artist Norman Rockwell, as a part of his Four Freedoms paintings, inspired by President Roosevelt’s State of the Union Speech in 1941. The President outlined in that speech what he termed the “four essential freedoms: freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom from want, freedom from fear.

In a poignant tribute to the painting which appeared in a recent issue of the Wall Street Journal, entitled Ode to Civil Discourse, the author, Bob Greene, noted several features which may not occur to an artist in current times:

If you’ve ever seen the painting, you know what I mean. The setting is a town meeting. One man, in work clothes, has risen from the audience to speak. There is nervousness, and courage, in his eyes; Rockwell makes it evident that the man is likely not accustomed to talking in public. Other citizens of the town, the men in coats and ties, are in the seats around him. Their eyes are focused upward, toward him. They are hearing him out; they are patiently letting him have his say.

His eyes, their eyes…that is the power of the painting. We, of course, have no idea what is on the man’s mind, or whether the other townspeople agree with him or adamantly oppose him. But as he talks they are listening, giving him a chance. They know that their own turn, if they want it, will come. For now, they owe him their full and polite attention.

The author notes, with a deep sadness I share, against the backdrop of the near-collapse of societal norms of civility we are now witnessing, that the “full and polite attention” they are giving him is such a simple concept, but one “that sometimes seems to be disappearing in this era when angry words hurtle past each other like poison-tipped arrows.”

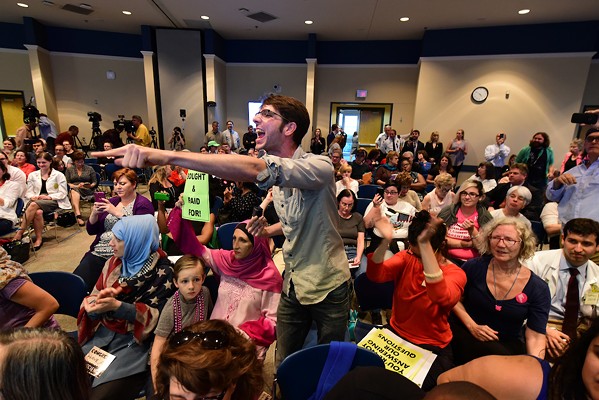

Nothing could more vividly illustrate the “mad dog” approach to modern speech than a photo I saw recently of a young man, apparently totally out of control, pointing his finger and screaming at our United States Senator, Bill Cassidy, and one of those (many!) –to use the media’s favorite euphemism—“raucous” Town Hall meetings.

If one wants a graphic illustration of how far this Nation has fallen, place the Rockwell painting side-by-side with the picture of this pathetic little – in so many ways- radical bleating and screaming and pointing at a United States Senator whose only crime is, so far as we know, to hold views different from those of the little radical. Two different pictures; two different worlds.

I write all of this as something in the nature of a backdrop for a tribute to a friend and respected colleague here in our community (let’s call him John, which works out well as his name is John) who has demonstrated such qualities of a true citizen, in speaking out against what he saw as wrong-headed and wasteful spending habits that he could be the model for the Rockwell painting. In fact, I have often told him that it has occurred to me that he is similar to the speaker in that painting even in his mode of dress!

We initially met on the occasion of my very first visit to a meeting of one of our public bodies; the reason I went to this meeting was that I had heard that some of the members of this particular Board were quite “high-handed” and autocratic toward any member of the public who had the temerity to express disagreement with their decisions.

So I, a retired trial lawyer with some experience with autocratic abuses of public trust, decided to go have a look for myself. What I saw, shortly after entering the Chamber (Star? I report, you decide.) was nothing less than astonishing, especially for someone who had a deep and abiding love for, and dedication to, the freedoms with which we have been gifted by our Founding Fathers. The friend of whom I write today went to the podium and got through a few sentences when the Chairperson told him, in effect, to “shut up and sit down”; when he persisted, as was his right as an American citizen, the Chair called upon a Deputy Sheriff with a Glock on his hip to remove him from the room. That was all I needed to see to affirm that this truly was out-of-control autocracy in action and, as I related later to a friend, “the lawyer kicked in” and in a few seconds I was at the podium reminding these petty little “Royals” of the Bill of Rights to the Constitution. At that point, I was also ordered to “shut up and sit down”, which order, of course, just made me more determined to continue speaking. In a matter of seconds, I felt the “long arm of the law” (quite literally!) on my shoulder, and I was also escorted out of the “Chamber”.

My friend John was not in the least intimidated by these Gestapo tactics, however, and returned almost every month to voice his objections, usually deeply researched and well founded, to their profligate spending and abuses of their office. I was privileged to attend some of those meetings with him and learned valuable lessons about both the value and the pain which goes with “petition[ing] the Government for a redress of grievances.”

The author of the Journal article posits a few thoughts about how Mister Citizen in the portrait might be received today:

That man standing up in “Freedom of Speech”—what would be his fate today, in a world where the town meeting is not limited to any single town, where the meeting never stops, never sleeps, where the attendees are routinely invisible and full of casual rage? Would the man be granted a courteous hearing? Or, depending on the point he was hoping to make, would he be hooted down, hounded and laughed at by an audience he couldn’t see? Would he be silenced by strangers?

It is because I mourn the loss of “reverence in all those eyes” and the fact that I also feel a deep “sanctity in the act of saying it” that I write of my friend and Mister Citizen in the painting and all of those remaining citizens who still stand up and look “the betters” in the eye. They, for the most part, in my experience, seek their “redress of grievances” with reason, logic, respect, dignity, courtesy and civility, and I pray that they, and not the “screamer” at the Senator’s Town Hall or the hoodlums at Middlebury or Berkeley, will represent the future of public discourse in the future.